Vanilla LLMs Are Not Fit for Medical Diagnosis

With language-based AI on the rise, many are projecting futures in which all sorts of fields are taken over by autonomous agents. Given the complexity and cost of healthcare in the U.S. specifically, it’s easy to hope for a future in which healthcare services are made more accessible and less expensive via an AI taskforce. While I agree with the sentiment that many healthcare tasks can be enhanced by modern language processing techniques (I’m betting my PhD on it), I worry that the magic of ChatGPT may have people convinced that “being a doctor” is a solvable task for existing generative language modeling tools. My worry is not unfounded, either; in April, the “infamous” Martin Shkreli released the world’s first AI doctor (or “virtual healthcare assistant,” for lack of a less legally-binding term). You can read all about that mess here.

In this post I’m going to argue that medical diagnosis is not a task which should be entrusted to current language models, despite the simplicity of treating it as a language-to-language task. As someone who has worked in healthcare and studies/writes about language modeling, I’m hoping I have something to add.

(I should mention that my intended audience of this post includes medical professionals, NLP researchers, people in-between and anyone who is interested in the future of AI generally. I don’t assume you have too much of a technical background - hopefully if you have one you’ll forgive me, and find my overview insightful anyway.)

Part 1: How We Got Here

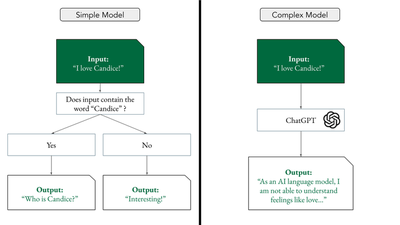

Generative language modeling is a sequence-to-sequence task in which human language (e.g. a ”prompt”) is taken as input and human language (e.g. a “response”) is given as output. Programs that perform this task are called generative language models (LMs). Existing LMs range in complexity from very simple to very complex.

In the last year, generative language modeling has received wide-spread attention in both scientific literature and popular media, largely due to the release of ChatGPT, a chat-oriented anthropomorphic language model which has achieved some pretty stunning results. This model (and others like it) are trained on copious amounts of human-written language, taken from the internet, which is one of the many reasons they can provide human-like responses to various prompts.

The beauty of ChatGPT from a technical perspective is that many difficult tasks can be made easy by expressing them in “plain English.” There have been and will be many tasks in which large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT achieve state-of-the-art performance, because there are a lot of reasoning tasks which can be easily formalized with human language inputs and human language outputs. These include some medical tasks, including responding to health questions on social media and even obtaining a passing grade on a practice versions of the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

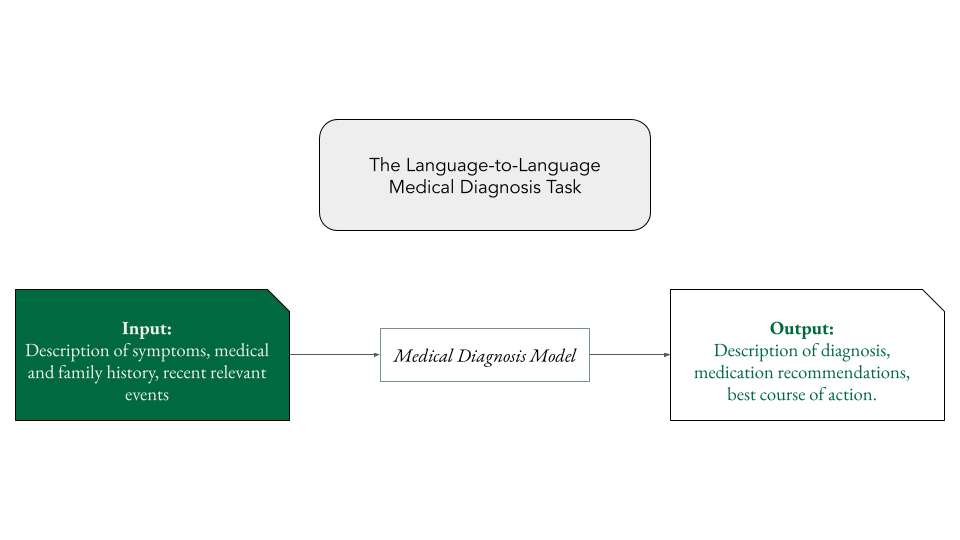

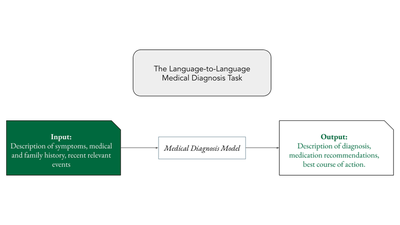

Medical diagnosis is an obvious candidate language-to-language task for LLMs to solve. When you go to the doctor you tell her in “plain English” what’s wrong. After some probing questions, some examination, and some expert-level thinking, she tells you in “plain English” what you need to do to feel better. Simple, right?

Perhaps, in theory. However, in practice there are some issues. For the purpose of my discussion, medical diagnosis is the task which takes as input a patient’s medical history, symptoms, and relevant experiences in the form of human language and outputs a treatment plan and diagnosis in human language. This is the simplest possible form of the task that care-providers perform yet, as we’ll see, it is a far too complicated for even the very best of our current LLMs.

Part 2: The Problem(s)

Problem 1: Unexpected Outputs

Perhaps the most famous problem with LLMs generally is their tendency to give responses that are off-topic. The term hallucination comes from the field of machine translation, i.e. the task which takes a text in language A as input and outputs a translation of the text in language B. In the task of machine translation, a model output contains a hallucination if anything appears in the translated text without appearing in the input text (see here). This term has evolved to mean any model output that is out-of-context, nonsensical, or — especially relevant for our discussion — unsupported by provided evidence.

In the context of medical diagnosis, hallucinations are particulary dangerous. For vanilla LLMs asked to perform the diagnosis task, this would include a) the tendency of the model to respond to symptoms not present in the patient’s input, b) model outputs which include impossible instructions or obviously wrong medications, and c) seemingly-correct model advice which is unsuported by provided medical literature. The last problem is particularly potent because LLMs have a propensity to sound confident, even when they are wrong. Patients who receive these types of hallucinated medical diagnoses would be vulnerable to dangerous side effects of medication non-adherence and undiagnosed illness.

While work has been done to stem the tide of hallucinations in LLMs, the reality is that current LLMs — even those which have been trained to attend to specific evidence — have little control over this phenomena compared to human expert. That alone is reason enough to stop the train of medical diagnosis via LLMs. We have no idea what this type of error would lead to in a deployed diagnosis model setting because this type of problem likely almost never exists with trained medical professionals.

Problem 2: LLMs Are Too Nice

Part of the long-term scientific contribution of ChatGPT was the realization that the standard language modeling objective could be jointly learned with another objective: to give people the answers they want, whenever possible. The process of teaching an LLM to give outputs which are helpful for humans is called reinforcement learning with human feedback, and it essentially involves humans scoring LLM responses based on how helpful they are across a number of human values like “helpfulness” and “harmlessness.” While there’s a lot of work being done on LLM alignment, or the task of aligning the outputs of an LLM with ideal human values, it is in no way a solved task.

Human care providers do a lot of hard, emotional work, which sometimes includes convincing their patients that they need to change their lifestyles. Current training objectives of LLMs simply do not align with this type of care.

Problem 3: Bad Actors

Not all users of your hypothetical medical diagnosis tool are going to be nice people with good intentions. LLMs trained with the objective of being helpful to the person behind the prompt are notoriously, erm, generous.

"Use LLMs in your customer support," they said pic.twitter.com/omRlAIXdYC

— Joseph Nelson (@josephofiowa) August 4, 2023

To put it bluntly, LLMs are far more susceptible to intentional misuse than human care-providers. If you ask your doctor to honk in-between words, she will laugh at your joke. If you ask your diagnosis tool to honk in-between words and claim it is a medical necessity, it will probably do it.

If you ask your doctor for a morphine prescription, she will make an expertly-informed decision with your short-term and long-term health in mind. If you ask your diagnosis tool for a morphine prescription and claim it is a medical necessity… You get the idea.

Part 3: What’s Next

Hopefully the problems I’ve described here have convinced you that current LLM technology is poorly suited for the medical diagnosis problem. There are myriad other problems that I haven’t discussed, such as our initial questionable assumption that medical diagnosis can even be appropriately approximated as a text input/text output task.

The reality is that any medical diagnosis tool based on recent LLM technology will fail to reliably replicate or approximate human-centered work forces. While work is still being done to mitigate the types of problems I’ve discussed here, there is a hype cycle in progress and we run the risk of damaging the current system in favor of a worse, cheaper system.

What are the solutions, you ask? I’m not sure. Textual anomaly detection (AD), the task of recognizing never-before-seen or semantically-outlying LLM outputs (or inputs) is an intriguing task which could be useful for finding both unexpected outputs and bad actors. However, current approaches to AD lack proper real-world evaluation, in my opinion, especially in the context of deployed LLMs. Progress in LLMs for knowledge-intensive tasks like medical diagnosis will almost certainly be multi-tiered, however. If there were a one-idea-fits-all-problems solution, it’d be done by now. I believe in the power and value of language processing techniques — I’m just hoping that more influential people are able to force themselves to be more skeptical, like me.