Costs of Calculating the Actual Causal Language Conditional Probabilities of English

Why can’t/don’t we determine the actual conditional probability distributions of the English language? (Inspired in part by this work by Benjamin LeBrun, Alessandro Sordoni, and Timothy J. O’Donnell, in which they estimate these probabilities and then estimate the estimates, showing along the way that modern architectures have some pretty basic language-fitting flaws.)

For simplicity, let’s make some standard-ish assumptions.

- We’re doing causal language modeling with a context length C, meaning we’re going to predict the next token in the sentence by conditioning on the prior C tokens.

- Each sentence is just a list of tokens, where the token is drawn from the set of M tokens that exist in English.

- We have a corpus of K sentences that make up the true “language” (this sounds like a huge jump, but it’s basically the same as assuming that Wikipedia + news articles + social media will be enough to teach a large language model English, which we do all the time).

- We take a maximum sentence length, call it N, and pad/truncate each sentence to that length.

Now we have K sentences of length N, where each sentence is made up of a list of tokens from a set of size M. To calculate the actual conditional probability of a given token in sentence, we consider the prior tokens as met conditions. We take the subset of every sentence in the language where the prior tokens are the same as the ones we’ve seen so far. Then it’s just a matter of counting each actual next token among those sentences in the subset, and dividing their counts by the size of the subset.

Let’s illustrate what I mean by this with an example, then we’ll look at the size of English and the size of common corpora and estimate how much it would cost. Then I’ll philosophize for a moment and get out of here.

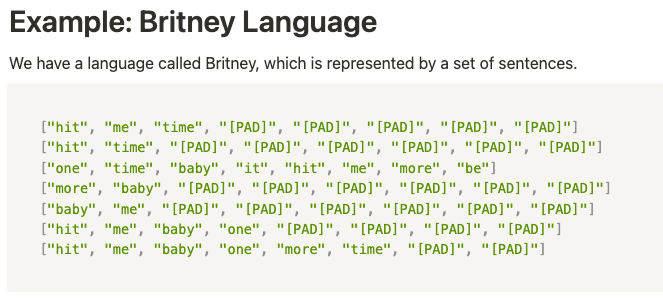

Example: Britney Language

We have a language called Britney, which is represented by a set of sentences.

["hit", "me", "time", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["hit", "time", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["one", "time", "baby", "it", "hit", "me", "more", "be"]

["more", "baby", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["baby", "me", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["hit", "me", "baby", "one", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["hit", "me", "baby", "one", "more", "time", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

Britney is a set of K = 7 sentences, where each sentence is a list comprised of N = 8 tokens (either truncated, or padded by the "[PAD]" token). Each token is drawn from the following set of M = 9 tokens.

{"baby", "hit", "me", "time", "one", "more", "it", "be", "[PAD]"}

Let’s calculate a token probability distribution of the token "baby" in that last sentence.

“hit me **baby** one more time”

Which, as you’ve noticed after tokenizing and padding, looks like this.

[”hit”, “me”, “**baby**”, “one”, “more”, “time”, “[PAD]”, “[PAD]”]

Conditional Probability

Our goal is to use a context window of C = 2 to produce a probability distribution over the M = 9 tokens in Britney, indicating the true likelihood of the next token following the specific subsequence ["hit", "me"]. This distribution is conditional on the prior C = 2 tokens in the sentence, and is a discrete probability distribution over all possible single-token outcomes.

First, let’s count the number of times in Britney that a sentence contains the subsequence["hit", "me"].

["**hit**", "**me**", "time", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["one", "time", "baby", "it", "**hit**", "**me**", "more", "be"]

["**hit**", "**me**", "baby", "one", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

["**hit**", "**me**", "baby", "one", "more", "time", "[PAD]", "[PAD]"]

There are 4 sentences here, which becomes the sample space of outcomes in Britney conditioned on the prior C = 2 tokens being ["hit", "me"].

Next, we create a list of all the tokens that follow the subsequence ["hit", "me"]:

["time", "more", "baby", "baby"]

We count the number of times each of the M = 9 tokens occurs:

{"baby": 2, "hit": 0, "me": 0, "time": 1, "one": 0, "more": 1, "it": 0, "be": 0, "[PAD]": 0}

And we normalize these counts to create a probability distribution:

{"baby": 0.5, "hit": 0, "me": 0, "time": 0.25, "one": 0, "more": 0.25, "it": 0, "be": 0, "[PAD]": 0}

This result is the “actual” conditional token probability distribution for the Britney language, given the context "hit me".

Result

This example result is unsurprising and relatively easy to calculate; it’s simply conditional probability. So, why did we do this?

Causal language modeling is the task of predicting the next token in the sequence, given some number of previous tokens (context). The whole goal of training a neural causal language model (like Llama or ChatGPT) is to estimate what we have easily counted in our example. Again: if we can count it, why do we care to estimate it?

My answer is two-fold. First, we can’t actually count it that well because we have a lot of written texts for languages like English. Second, most of the time we don’t actually want a true probability distribution; we want an estimate with several hard-to-define properties.

Space and Time Cost Estimates

To figure out the cost of causal language modeling in our setup, we need to come up with estimates for the context length C, the number of total tokens M, and then some good estimate for the total number of tokens (# of documents K multiplied by the average # of tokens per document N).

The context length C is easy; we set it ourselves and it varies from model to model. GPT-4 has a context length of 8,000 and ChatGPT is 4,000. The smallest LLaMA model, LLaMA 7B, has a context window of 4,000. OpenAI recently released a model variant with a context length of 32,000, which is a small part of a larger push from the LLM community to get larger context lengths.

In English, depending on how tokenization (the process of turning texts into lists of tokens) is done, there are typically around M = 20,000 - 200,000 tokens. This means the size of each discrete token probability distribution, returned by the causal language model, is fairly large but still doable on a single machine.

Now to the part which really puts the impossibility of this task into perspective. The cost of iterating over something the size of a language is impossible. Llama 2 was trained on 2,000,000,000,000 tokens. Running a cost analysis, it takes O(C * K * N) to gather every context length C in a collection of tokens sized (K * N). If we took a typical context length of C = 4,000 tokens, and considered English well-approximated by the Llama 2 training corpus of K * N = 2,000,000,000,000, we would have to do around 8,000,000,000,000,000 operations to gather conditions for every token probability distribution. Then we’d have to actually do the counting, which at 8 quadrillion tokens in linear construction time, is impossible.

Let’s take it one step further to put it into perspective. Let’s just assume we can meet the space requirements (which is obviously impossible without distributed computing) because we have a really cool unlimited RAM machine. Now we actually need to do 16 quadrillion operations on a laptop. According to a fun post from 2013, which is a bit outdated now, 1 quadrillion operations took around 6.5 days. So 16 quadrillion operations would take… carry the 1… 104 days?

Token Probability Estimate Properties We Actually Care About

Look, this is dumb. 104 days and several terabytes of storage to calculate a single “true” conditional token probability distribution in English? What would that even give us?

The nice thing is, we don’t really care about the “true” probability of English (or any language) because… it’s not really that true! Languages, as human communication devices, are not fully expressed in written texts. We can’t know the “true” conditional probability distribution of any token in English because it’s not actually expressed on the page, it’s in a pre-expressed state in the collective mind of English-speaking humankind.

Okay, well, then why do we care about estimating these probability distributions when we’re building language models? What do we care about?

We care about making language tasks easier for humans. Specifically, we care about generating language that is human-like enough to help us think through things, write things, express things, and come up with new things.

But when humans generate language, they don’t stop midway through a sentence, define a probability distribution over all the possible words they could choose next, and and take the word with maximum probability. Humans are creative! I think there is probably a human correlation between creativity and ignoring token probability priors! Better yet, there’s probably a human correlation between creativity and not even understanding why you would care about token probability priors!

We don’t want perfect causal language approximators. We want causal language approximators that are creative when they need to be, accurate when they need to be, helpful when they need to be (and not helpful when they need to not be), and safe.

So, let’s do that instead.